multithreading Getting started with multithreading

Remarks

Multithreading is a programming technique which consists of dividing a task into separate threads of execution. These threads run concurrently, either by being assigned to different processing cores, or by time-slicing.

When designing a multithreaded program, the threads should be made as independent of each other as possible, to achieve the greatest speed-up.

In practice the threads are rarely fully independent, which makes synchronisation necessary.

The maximum theoretical speed-up can be calculated using Amdahl's law.

Advantages

- Speed up execution time by using the available processing resources efficiently

- Allow a process to remain responsive without the need to split lengthy calculations or expensive I/O operations

- Easily prioritize certain operations over others

Disadvantages

- Without careful design, hard-to-find bugs may be introduced

- Creating threads involves some overhead

Can the same thread run twice?

It was most frequent question that can a same thread can be run twice.

The answer for this is know one thread can run only once .

if you try to run the same thread twice it will execute for the first time but will give error for second time and the error will be IllegalThreadStateException .

example:

public class TestThreadTwice1 extends Thread{

public void run(){

System.out.println("running...");

}

public static void main(String args[]){

TestThreadTwice1 t1=new TestThreadTwice1();

t1.start();

t1.start();

}

}

output:

running

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.IllegalThreadStateException

Deadlocks

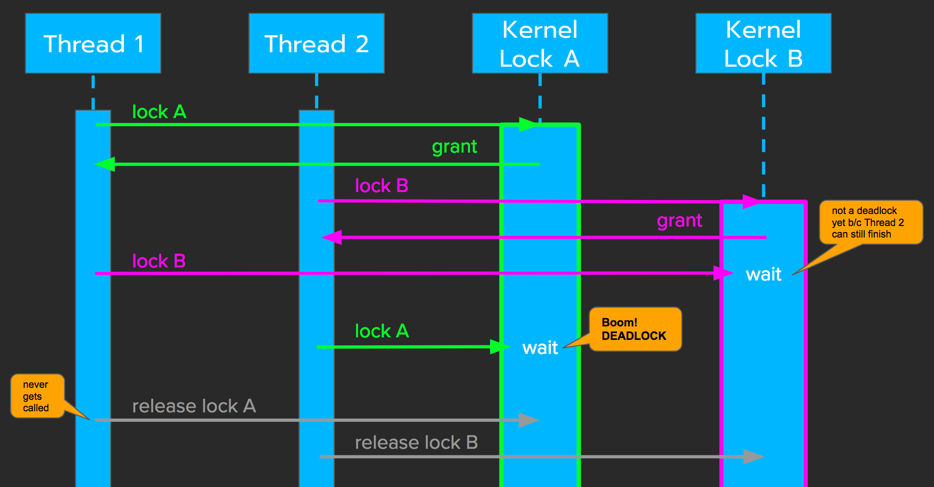

A deadlock occurs when every member of some group of two or more threads must wait for one of the other members to do something (e.g., to release a lock) before it can proceed. Without intervention, the threads will wait forever.

A pseudocode example of a deadlock-prone design is:

thread_1 {

acquire(A)

...

acquire(B)

...

release(A, B)

}

thread_2 {

acquire(B)

...

acquire(A)

...

release(A, B)

}

A deadlock can occur when thread_1 has acquired A , but not yet B , and thread_2 has acquired B , but not A . As shown in the following diagram, both threads will wait forever.

How to Avoid Deadlocks

As a general rule of thumb, minimize the use of locks, and minimize code between lock and unlock.

Acquire Locks in Same Order

A redesign of thread_2 solves the problem:

thread_2 {

acquire(A)

...

acquire(B)

...

release(A, B)

}

Both threads acquire the resources in the same order, thus avoiding deadlocks.

This solution is known as the "Resource hierarchy solution". It was proposed by Dijkstra as a solution to the "Dining philosophers problem".

Sometimes even if you specify strict order for lock acquisition, such static lock acquisition order can be made dynamic at runtime.

Consider following code:

void doCriticalTask(Object A, Object B){

acquire(A){

acquire(B){

}

}

}

Here even if the lock acquisition order looks safe, it can cause a deadlock when thread_1 accesses this method with, say, Object_1 as parameter A and Object_2 as parameter B and thread_2 does in opposite order i.e. Object_2 as parameter A and Object_1 as parameter B.

In such situation it is better to have some unique condition derived using both Object_1 and Object_2 with some kind of calculation, e.g. using hashcode of both objects, so whenever different thread enters in that method in whatever parametric order, everytime that unique condition will derive the lock acquisition order.

e.g. Say Object has some unique key, e.g. accountNumber in case of Account object.

void doCriticalTask(Object A, Object B){

int uniqueA = A.getAccntNumber();

int uniqueB = B.getAccntNumber();

if(uniqueA > uniqueB){

acquire(B){

acquire(A){

}

}

}else {

acquire(A){

acquire(B){

}

}

}

}

Hello Multithreading - Creating new threads

This simple example shows how to start multiple threads in Java. Note that the threads are not guaranteed to execute in order, and the execution ordering may vary for each run.

public class HelloMultithreading {

public static void main(String[] args) {

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

Thread t = new Thread(new MyRunnable(i));

t.start();

}

}

public static class MyRunnable implements Runnable {

private int mThreadId;

public MyRunnable(int pThreadId) {

super();

mThreadId = pThreadId;

}

@Override

public void run() {

System.out.println("Hello multithreading: thread " + mThreadId);

}

}

}

Purpose

Threads are the low level parts of a computing system which command processing occurs. It is supported/provided by CPU/MCU hardware. There are also software methods. The purpose of multi-threading is doing calculations in parallel to each other if possible. Thus the desired result can be obtained in a smaller time slice.

Race conditions

A data race or race condition is a problem that can occur when a multithreaded program is not properly synchronized. If two or more threads access the same memory without synchronization, and at least one of the accesses is a 'write' operation, a data race occurs. This leads to platform dependent, possibly inconsistent behavior of the program. For example, the result of a calculation could depend on the thread scheduling.

writer_thread {

write_to(buffer)

}

reader_thread {

read_from(buffer)

}

A simple solution:

writer_thread {

lock(buffer)

write_to(buffer)

unlock(buffer)

}

reader_thread {

lock(buffer)

read_from(buffer)

unlock(buffer)

}

This simple solution works well if there is only one reader thread, but if there is more than one, it slows down the execution unnecessarily, because the reader threads could read simultaneously.

A solution that avoids this problem could be:

writer_thread {

lock(reader_count)

if(reader_count == 0) {

write_to(buffer)

}

unlock(reader_count)

}

reader_thread {

lock(reader_count)

reader_count = reader_count + 1

unlock(reader_count)

read_from(buffer)

lock(reader_count)

reader_count = reader_count - 1

unlock(reader_count)

}

Note that reader_count is locked throughout the whole writing operation, such that no reader can begin reading while the writing has not finished.

Now many readers can read simultaneously, but a new problem may arise: The reader_count may never reach 0 , such that the writer thread can never write to the buffer. This is called starvation, there are different solutions to avoid it.

Even programs that may seem correct can be problematic:

boolean_variable = false

writer_thread {

boolean_variable = true

}

reader_thread {

while_not(boolean_variable)

{

do_something()

}

}

The example program might never terminate, since the reader thread might never see the update from the writer thread. If for example the hardware uses CPU caches, the values might be cached. And since a write or read to a normal field, does not lead to a refresh of the cache, the changed value might never be seen by the reading thread.

C++ and Java defines in the so called memory model, what properly synchronized means: C++ Memory Model, Java Memory Model.

In Java a solution would be to declare the field as volatile:

volatile boolean boolean_field;

In C++ a solution would be to declare the field as atomic:

std::atomic<bool> data_ready(false)

A data race is a kind of race condition. But not all race conditions are data races. The following called by more than one thread leads to a race condition but not to a data race:

class Counter {

private volatile int count = 0;

public void addOne() {

i++;

}

}

It is correctly synchronized according to the Java Memory Model specification, therefore it is not data race. But still it leads to a race conditions, e.g. the result depends on the interleaving of the threads.

Not all data races are bugs. An example of an so called benign race condition is the sun.reflect.NativeMethodAccessorImpl:

class NativeMethodAccessorImpl extends MethodAccessorImpl {

private Method method;

private DelegatingMethodAccessorImpl parent;

private int numInvocations;

NativeMethodAccessorImpl(Method method) {

this.method = method;

}

public Object invoke(Object obj, Object[] args)

throws IllegalArgumentException, InvocationTargetException

{

if (++numInvocations > ReflectionFactory.inflationThreshold()) {

MethodAccessorImpl acc = (MethodAccessorImpl)

new MethodAccessorGenerator().

generateMethod(method.getDeclaringClass(),

method.getName(),

method.getParameterTypes(),

method.getReturnType(),

method.getExceptionTypes(),

method.getModifiers());

parent.setDelegate(acc);

}

return invoke0(method, obj, args);

}

...

}

Here the performance of the code is more important than the correctness of the count of numInvocation.